Song of the Week: 4/14-4/20-2025

Emmylou Harris, Ricky Skaggs and Dolly Parton: "Green Pastures"

Early Saturday morning I found myself standing in a green green pasture in Oley, PA at 5:40 am staring at clouds bracing across the cat’s eye of the moon. The baby blues of the sky set against the green pasture running into the horizon lifted my heart into some heaven that an astronaut would long to explore.

On Good Friday I like to re-read Hemingway’s “Today is Friday.” The genius of the story is that is that it is set in the aftermath of Christ’s crucifixion. Putting Hemingway’s story into context the critic Joseph Flora writes,

No single death in history is more familiar to the world than that of Jesus. By the Middle ages, artists and writers were drawn to that death. During the Renaissance painters, musicians, and poets often made it central to their work. Like the majority of his readers, since early childhood Hemingway had been aware of Jesus’ death and the orthodox version of its meaning. Visits to the Art Institute of Chicago and the events of Jesus’ life that he read about in the Gospels cold be viewed in different ways. Later, as a young writer in the 1920s close to the pulse of high modernism, Hemingway was aware that all orthodoxies had been brought into doubt. He was also aware that Jesus’ story was receiving various treatments from many of the writers in the vanguard. Any careful reader of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the essential modernist poem, encountered a lament for a culture in decay without a vital Christian force. In 1923 Wallace Stevens in his poem “Sunday Morning” offered a more upbeat portrayal of the world without the Christian God. But Steven’s protagoinst remains haunted by the tomb of Jesus in Palestine as she longs for “some imperishable bliss.” Somewhat earlier, in 1909, Ezra pound had published the hugely popular “Ballad of the Goodly Fere” in which he portrays a workingman’s Jesus who stands up to the establishment and goes bravely to his death on “a tree” and whom the cowards cannot conquer.

When I teach the story, I ask my students to try to consider the three Roman soldiers talking about the crucifixion like a great boxing match in a bar the night Jesus dies. One soldier is a skeptic:

Why didn’t he come down off the cross?

One admires Christ:

He was pretty good in there today.

One seems to be convicted by what he witnessed:

I feel like hell.

One particular exchange between two of the soldiers always captures me:

What became of his gang?

Oh, they faded out. Just the women stuck by him.

They were a pretty yellow crowd. When they seen him go up there they didn’t want any of it.

The women stuck all right.

J. D. Salinger offers his own take on the crucifixion and the women of Galilee in his story “De Daumier Smith’s Blue Period” through a description of a painting by a nun named Sister Irma.

Her best picture was done in water colors, on brown paper . . . The picture, despite its confining size (it was about ten by twelve inches), was a highly detailed depiction of Christ being carried to the sepulcher in Joseph of Arimathea’s garden. In the far right foreground, two men who seemed to Joseph’s servants were rather awkwardly doing the carrying. Joseph (of Arimathea) followed directly behind them—bearing himself, under the circumstances, perhaps a trifle too erectly. At a respectable subordinate distance came the women of Galilee, mixed in with a motley, perhaps gate-crashing crowd of mourners, spectators, children, and no less than three frisky, impious mongrels. For me, the major figure in the picture was a woman in the left foreground, facing the viewer. With her right hand raised overhead, she was frantically signalling to someone—her child, perhaps, or her husband, or possibly the viewer—to drop everything and hurry over. Two of the women, in the front rank of the crowd, wore halos. Without a Bible handy, I could only make a rough guess at their identify. But I immediately spotted Mary Magdalene. At any rate, I was positive I had spotted her. She was in the middle foreground, walking apparently self-detached from the crowd, her arms down at her sides. She wore no part of her grief, so to speak, on her sleeve—in fact, there were no outward signs at all of her late, enviable connections with the Deceased.

In the Gospel of John 20.1-8 it is written:

Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb. So she ran and went to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved, and said to them, “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.” So Peter went out with the other disciple, and they were going toward the tomb. Both of them were running together, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. And stooping to look in, he saw the linen cloths lying there, but he did not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen cloths lying there, and the face cloth, which had been on Jesus' head, not lying with the linen cloths but folded up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who had reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed.

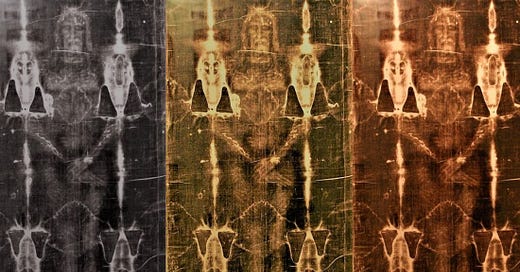

Yesterday I listened to a scholar, Dr. Jeremiah Johnston, speak about this passage with regards to the Shroud of Turin and the way the disciples look at the linen cloths laying there and the face cloth. Listen at the 7:00 min mark:

The writer C. S. Lewis kept a photograph of the 1931 picture of the Shroud by Giuseppe Enri above his mantle at The Kilns:

In Lewis’ book Till We Have Faces he writes:

The sweetest thing in all my life has been the longing — to reach the Mountain, to find the place where all the beauty came from — my country, the place where I ought to have been born. Do you think it all meant nothing, all the longing? The longing for home? For indeed it now feels not like going, but like going back.

When Mary and the women of Galilee approached the tomb of Jesus it was 5:43 am, before the sun had risen.

Standing in the pasture in Oley, PA the ocean of the land rose up to greet the horizon’s blue and the white cat’s eye of the moon beyond the clouds. I could feel the sun rising even in the darkness of the hour.

The writer Phillip K. Dick had a theory about time:

The idea . . . is we're all living in 50 AD, where Jesus Christ has just died on the cross, saving us, allowing us to have eternal lives if we choose to follow Him, but Satan/evil is trying to get us to forget this with an illusion of time. In effect, time is just us being asked if you choose to follow Him or not, and our life is just saying "no," "no," "no" until you say "yes."

Ecce Homo.

“Green Pastures”

Troubles and trials often betray those

On in the weary body to stray

But we shall walk beside the still waters

With the Good Shepherd leading the way

Those who have strayed were sought by the Master

He who once gave His life for the sheep

Out on the mountain, still He is searching

Bringing them in forever to keep

Going up home to live in green pastures

Where we shall live and die nevermore

Even the Lord will be in that number

When we shall reach that heavenly shore

We will not heed the voice of the stranger

For he would lead us on to despair

Following on with Jesus our savior

We shall all reach that country so fair

Going up home to live in green pastures

Where we shall live and die nevermore

Even the Lord will be in that number

When we shall reach that heavenly shore