In an attempt to illustrate the difference between noir and hard-boiled fiction Al Guthrie once stated, “the crucifixion is noir, the resurrection is hard boiled.” There is perhaps no scene in Jean-Pierre Melville’s oeuvre which better illustrates his sense of noir than the opening of his 1969 masterpiece Army of Shadows, a film that documents La Résistance in France from 1942-43. As the scene opens, the Arc de Triomphe looms over a completely desolate Paris, and the German army marches around the Arc and proceeds down the Champs-Élysées. The eye of the camera never shifts, but as the German soldiers approach and ultimately overwhelm the view of the Arc de Triomphe, the frame freezes and the primary action of the film begins with a shot a French countryside in a downpour and a police wagon moving down a muddy road. In the wagon is Phillippe Gerbier, a member of la Résistance, being escorted by two French Vichy cops to an internment camp. The opening scene, juxtaposed against the German army and German music, depicts the dark cloud that has fallen over France, a cloud brought on by the Germans that represents the internal struggles within France to survive and resist the German occupation.

The opening recalls in some ways, though not in tone, the scene in Casablanca when Victor Laszlo leads the band in “La Marseillaise” to drown out the German officers singing “Die Wacht am Rhein.”

Casablanca however, depicts a resurrection, Army of Shadows is pure crucifixion, pure noir. The film closes with the depiction of how the four principle figures of la Résistance depicted in the film die, scenes which are inter-spliced with title cards. The final scene shows Philippe, captive yet again in the back of a car, with a final shot from Philippe’s perspective of the Arc de Triomphe looming over a German officer directing traffic as he heads to his death.

When Melville showed the film to Joseph Kessel, the author of the book from which the film was adapted and took its title, Kessel was moved by the closing scene, and, according to Melville, “When he read the words announcing the deaths of the four characters, he was unable to stop himself from sobbing. He was not expecting those four lines, which he had not written.” Melville continues, “In order to make a true film about la Résistance a lot of people would have to be dead. Don’t forget that there were more people who did not work for la Résistance than people who did.”

Understanding the people who worked for la Résistance and the conviction of the belief with which they fought is central to understanding Melville’s code. The code is difficult to understand, of course, because the world that Melville loves and re-creates does not exist anymore and to compare it to the modern world would be impossible because of entanglements with pride. “The war turned everything upside-down, you know,” Melville once told Rui Nogueira, “A whole world disappeared, making way for another which is still in a state of formation.” The worlds, old and new, that Melville refers to here are best understood through his relationship with death. “Tragedy,” he states, “is the immediacy of death that you get in the underworld, or at a particular time such as war . . . the characters from Army of Shadows are tragic characters; you know it from the very beginning.” Seen in this light, Melville is a poet of the underground, for a world in which the pre-WWII world is dead and he is the author of this tragedy.

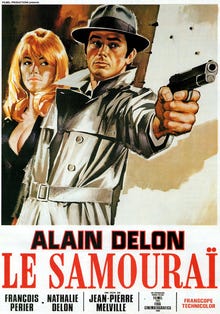

Consider the epigraph Melville employs for Army of Shadows: “mauvais souvenirs, soyez pourtant les bienvenus . . . vos etes ma jeunesse lointain” (“unhappy memories! Yet I welcome you . . . you are my long lost youth”). “The war was awful, horrible . . . and marvelous . . . I don’t want to situate my heroes in time,” Melville once said when speaking of his film Le Samouri, “I don’t want the action of a film to be recognizable as something that happens in 1968.” Melville’s sense of time and transposition often estranged him from the world of French cinema. It was not just Melville’s love of American cinema and use of American tropes in his films that alienated him, but his refusal to wallow in the passing political squabbles of his day within his medium. Critic Amy Taubin illustrates these political squabbles well when she points out that Army of Shadows was not received well in 1969 because French critics “savaged the film for what they saw as its glorification of General Charles de Gaulle, who, then president, was despised as the betrayer of the May 1968 student uprising.”

Thus, central to Melville’s code is the role of an artist above all, and even though he did not believe that as a filmmaker he could attain the artistic height of an author, his films were crafted in pursuit of the same heights of immortality that he saw in his heros of the literary world. In fact, Melville had such admiration and reverance for Herman Melville that he took his name as his own. In an interview with Gideon Bachman for the radio show “Film Art” on WBAI in New York, Melville explained why he became a filmmaker, citing American film directors and the films they made before the war. Along these lines, when Bachmann asks how Melville is able to make films that move with a “clipped and rhythmic sharpness,” Melville replies, “it is easier to make a film. It is more difficult to write a good story, to be a man like Faulkner or Hemingway or Dos Passos.” Melville falls into Faulkner’s definition when he writes that: “the aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life. Since man is mortal, the only immortality possible for him is to leave behind something that is immortal since it will always move.” So for Faulkner motion was arrested in Yoknapatapha; for Melville it was arrested within, as Luc Sante puts it when talking about Bob Le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler), “a bygone, pre-war world.” Melville’s characters are made up part and parcel within this world, the world that existed before the post-war world began to exist. It is fitting that Melville’s second life as an artist in the recent revival (Army of Shadows was only released in America for the first time in 2006) is a testament to how his films “move again,” to borrow a line from Faulkner, over half a century after he began to make them.

Even when addressing the most lighthearted of his gangster films, Bob the Gambler, Melville’s sense of the human tragedy is evinced: “There’s always a Bridge on the River Kwai sleeping deep inside me” he says, “I like the uselessness of effort: the uphill road to failure is a very human thing. Scientists, for instance, push research so far that there will inevitably come a point when they can suddenly go no further. Man wants to go on to conquer every star in the solar system, but I think he’ll lose his bearings. Science progresses until it suffers a setback. In moving from achievement to achievement, man comes inevitably to his last, absolute defeat: death!” “Even so,” he adds, “Bob is still a lighthearted film.” But it is revealing that the gangster films that follow Bob the Gambler are not lighthearted. Even as Sante points out that Bob the Gambler is “impeccably hard-boiled,” he adds that it is “a valentine to a romantic Paris now two or three times removed from our own purview” and that “its romance can outshoot any lesser picture’s cynicism.” Still, even if Bob the Gambler is his “hardboiled” opus, his resurrection if you will, all of the tropes of the noir films that will follow are present within the film. Melville clearly illustrates the human tragedy present within Bob the Gambler, but the tragedy is enacted in the codes of the characters. For instance, Bob tells his young assistant Paulo not to associate with another gangster because he is a pimp and beats women. Melville’s response to the eroticism in Bob the Gambler, something often lacking in his later films, is also revealing: “We’re a long way from the famous Hollywood cinema of the ‘30s, where eroticism existed on a different level. It was a respectable eroticism that flattered the sexual instincts of men and women. There was more eroticism then, when women appeared fully dressed on the screen, then now when they are often completely nude.” This attitude towards eroticism is clear in Bob’s adherance to a code and his mentorship of Paulo.

Furthermore, Melville reveals one of his most important motifs, the relationship between gangsters and cops. As Melville puts it, “Gangsters have always had a fellow feeling for cops, and cops have always had a fellow feeling for gangsters. They’re in the same business. They exist in relation to each other.” The relationship between gangsters and cops is made all the more poignant because Melville does not “believe in friendship, not masculine friendship between gangsters or any other kind . . . Rather than friendship, there’s a community of interest in the underworld.” This community is clearly illustrated in Melville’s film Le Deuxiéme Souffle (The Second Wind) which Melville calls “film noir” in contrast with the comedy of manners within Bob Le Flambeur (think Oceans Eleven—a film which Melville accused of plagiarizing Bob). Like the protagonist Jef (played by Alain Delon) in Le Samouri, the central charater of Souffle is Gu, who has escaped from prison after ten years, a time that serves as a “reprieve” from his certain fate, his “second wind.” In writing about The Second Wind, Adrian Danks describes Gu as a “brutal, driven, and pared-down figure who gains respect, even from Inspector Blot . . . because he ultimately conforms to and doesn’t break from his ‘code.’ In fact, the key crisis for this character occurs after he is tricked by the police into informing on his criminal collaborators. His hysterical reaction, including an attempt at suicide, underlies the definitional importance of his inscrutable ethical code. But this code or typology is also central to the ethics of the film, and Gu is rewarded with a degree of respect and a heroic death for maintining it.”

Melville employs this same code in Le Samouri. It is worth noting that Melville once stated that all of his films were “transposed Westerns,” but he did not believe that a filmmaker could “make a Western outside America.” In speaking of Le Samouri, filmmaker John Woo cites an Eastern proverb that is given at the beginning of the film and writes that Melville, “understood Chinese philosophy even more than our own people. I think that I relate to his movies because his vision of humanity is so rooted in the Eastern tradition. His characters are not heroes; they are human beings. In the gang world, they have to stick to the rules, but they remain faithful to a code of honor that is reminiscent of ancient chivalry.” Woo’s commentary on Melville’s understanding of Eastern culture, and his vision of humanity is even more fascinating when considering Melville’s own commentary on the Eastern proverb that is cited from The Book of Bushido at the beginning of the film—“There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai, unless perhaps it be that of the tiger in the jungle.” As Melville tells Nogueira, “Do you know that the film was shown in Japan complete with that opening title, which I attribute to The Book of Bushido? What they don’t know is that I wrote the ‘quotation.’”

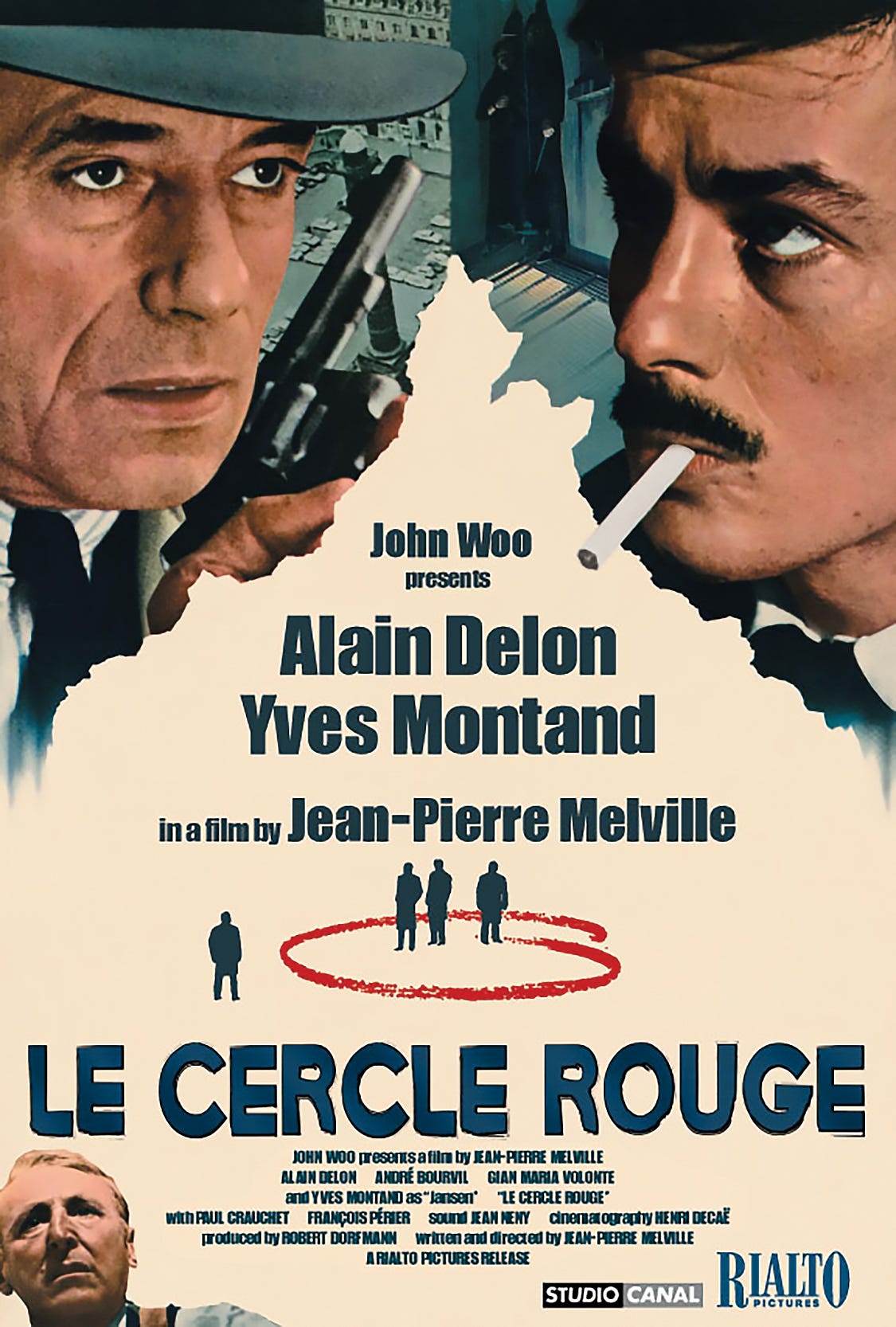

Similarly, Melville makes up a quote by Siddhartha that serves as the epigraph of the film that followed Army of Shadows, his 1970 noir masterpiece Le Cercle Rouge (The Red Circle). The epigraph reads: “When men, even unknowingly, are to meet one day, whatever may befall each, whatever their diverging paths, on the said day, they will inevitably come together in the red circle.” Like Army of Shadows, The Red Circle is a culmination of Melville’s life’s work and his artistic code. As Michael Sragow observes, “Melville set out to synthesize all the thoughts and feelings he’d acquired about cops and robbers in fifteen years of genre movie making and a lifetime of movie watching. He emerged with something greater than a summing up.” Watching The Red Circle, it is clear that Melville is “il migglio fabbro.” One of the striking things about the film is the way it serves as a precursor to the great films of the 1970s. In The Red Circle it is clear that Melville’s mode of story telling certainly leaves a mark on American film in the 70s, much in the same way that American films of the 30s paved the way for him.

According to Michael Sragow, “with Le Cercle Rouge, Melville hikes to the fictional heights of his adopted namesake . . . Alain Delon’s Corey and his crew pulling off an epochal Paris jewelry heist may not seem as grand as Ahab and his crew harpooning Moby Dick. Yet the director imagines the preparation, execution and aftermath of Corey’s quest with such an unerring command of human and technical detail that the film becomes a metaphoric net capturing everything the auteur intuits about hubris, strength and fallibility . . . In both these works, the creators’ cunning combination of hardscrabble physical authority and characters that prompt identification with their honor and their weakness compel audiences to enter a world of genuine moral ambiguity.”

Moral ambiguity, though, is not amorality, as Sragow points out, “if the bourgeois viewers of Le Cercle Rouge find themselves alarmingly sympathetic to these bandits, it’s because they navigate ethically compromised waters that register as a true, if bleak, projection of a polluted social mainstream . . . Le Cercle Rouge . . . proves rigorously moral in its dramatic evaluation of five men and their responses to a heist and its aftermath.” This is hardly surprising to those who understand Melville’s code. Those who would accuse Melville of amorality do not understand the human condition. “I am a man like the rest, no better and no worse,” Melville once said, “I accept this human condition with all that it implies.” From this point of view, The Red Circle considers our common fate. At one point the head of Internal Affairs accuses all men of being guilty: “They’re born innocent, but it doesn’t last.” The chief investigator, Mattei is not convinced until the conclusion of the film when he confesses that his boss was right: “innocence doesn’t last, so all men are guilty.” But Sragow turns to Moby Dick and says that Melville, as a poet of the underground, ultimately reorients the question back on the audience: “Where do murderers go, man! Who’s to doom when the judge himself is dragged to the bar.” To which I can only answer Sragow from the abyss: the answer is in the red circle, man! The crucifixion is noir, the resurrection is hard boiled.

Coming soon:

Exploring the Influence of Ernest Hemingway upon the auteurship of Wes Anderson (Part I)